Features

Agronomy

Landscaping

Chinch bugs posed big problem in 2020

The No. 1 insect pest during 2020 in residential lawns was the hairy chinch bug

May 13, 2021 By Dr. Jesse Benelli, Bayer Environmental Science

Close-up of an adult chinch bug on a leaf. Photo courtesy of Dr. Jesse Benelli

Close-up of an adult chinch bug on a leaf. Photo courtesy of Dr. Jesse Benelli Move over Japanese beetles. Step aside European chafers and all other scarab beetles. Undoubtably, the No. 1 insect pest during 2020 in residential lawns was the hairy chinch bug.

Individually, they are small, minuscule surface feeder pests. Their power lies in their numbers, and in 2020 it felt like their populations exploded. Left in their wake were merely the unrecognizable remains of what once were beautifully manicured lawns.

What happened? Why was 2020 so extraordinary for chinch bugs? Will it happen again? This article hopes to shed light on these questions as we put 2020 in the rear-view mirror and begin the growing season of 2021.

Background

History and distribution. Chinch bugs are native to North America and are found across most regions of Canada, the United States and Mexico. The term “chinch bugs” is a generalized name that groups together all species of this pest. There are several different species of chinch bug that reside in different geographic regions. Hairy chinch bug (Blissus leucopterus) is the dominant species in Eastern Canada. In Western Canada, the dominant species may be the western chinch bug (Blissus occiduus).

Identification. First instar nymphs are orange with a beige stripe that runs horizontally across the mid-section. More importantly, first instar nymphs are incredibly small, with most of them being just under one millimetre in length. As nymphs mature in size, the orange colour gradually gives way to more of a dark brown to grey appearance. It is not until the fifth instar stage when wing pads are fully distinguishable and the overall colour of the chinch bug is black.

Lifecycle. In the spring, chinch bug adults migrate into lawns to begin feeding and mating. Females lay eggs when daytime temperatures exceed 15 degrees Celsius. For most regions in Canada, eggs will hatch in early-to-mid June, depending on the weather. Chinch bugs will complete five nymphal stages before maturing into adults by mid-to-late August. In years with sustained heat, a second generation can begin, but these second-generation nymphs will not successfully overwinter into the following year.

Feeding. Nymphs and adults have piercing-sucking mouthparts that injure turf by withdrawing sap from leaf, sheath, crown and stem tissues. During feeding, chinch bugs inject salivary toxins into the plant, causing coagulation within stem and leaf tissue, which affects the plant’s ability to transport water and nutrients.

Damage. Initial symptoms of chinch bug feeding include reddish purple discolouration of the leaf blade margins. As damage progresses, the affected leaves turn yellow, and thinning can be observed. As feeding intensifies, plants begin to turn straw colour and do not respond quickly to irrigation or fertilization inputs. If left untreated, large swaths of turf will decline and death can occur. Plants grown on south-facing slopes that receive full sun are at most risk of decline.

Scouting. Chinch bugs are most active during the early afternoon hours when it is sunny and warm. Adults can be seen in the spring on grass blades and nearby structures such as patios, decks, foundation walls, and fencing. Nymphs are much harder to see, and will be present from mid-to-late June through August. Nymphs tend to feed very close to the base of the plant stem. In late spring and early summer, it is important to get close to the ground and peel away the thatch material to scout for chinch bug nymphs.

Why were chinch bugs so devastating in 2020?

High number of overwintering adults. The summer of 2019 brought well above-average temperatures for much of Ontario, Quebec and the Maritimes. This weather was very conducive for the proliferation of chinch bugs. In correspondence with several lawn care operators, the summer of 2019 was (at the time) the worst year for chinch bugs in more than a decade. This likely resulted in very high populations of chinch bugs that overwintered heading into the 2020 season.

Late spring warmth accelerated egg laying and egg hatch. Air temperatures throughout Eastern Canada started off well below average in early spring. However, this soon gave way to record-setting warmth by the end of May. Hot and dry weather accelerates all aspects of their behavior and lifecycle. The timing of the record-setting heat during late spring couldn’t have been more perfect for accelerated egg laying, egg hatch, and an explosion of chinch bug nymphs.

Dry weather increased chinch bug survival. In 2020 hot weather was met with moderate to severe drought in parts of Eastern Canada. Chinch bugs will proliferate more readily in conditions of low soil moisture. In addition, low soil moisture can diminish the natural spread and infection of the pathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana. Furthermore, researchers recognize that flooding rains during spring can “drown out” chinch bug eggs and nymphs. Unfortunately, those flooding rains never happened. Undoubtably, the hot and dry weather caused not only higher populations of chinch bugs, but also inhibited many factors that lead to natural death of the chinch bug population.

Summer turfgrass decline was also a culprit. Many of our cool season turfgrasses reach peak physiological condition when mean air temperatures are between 18 and 22 degrees Celsius. The turf also needs adequate sunlight, nutrients, and water, the latter of which became increasing hard to come by during the season. Keeping the lawns adequately hydrated during the 2020 season was exceptionally difficult, if not impossible. This resulted in an already exhausted turf system having to endure a fight for its life. And in 2020, the chinch bug won.

Control solutions may have been applied too late. The warm and dry weather in May and June accelerated the lifecycle and behavior of chinch bugs. Being just two weeks late on an insecticide spray could have huge ramifications on achieving satisfactory chinch bug control.

Chinch bug populations can increase rapidly during the first five weeks following initial egg hatch. Studies in Ohio have reported that first instar nymphs showed population increases from 25 to 60 times in the two weeks following initial appearance.

This means that their nymphal populations can literally double each day soon after hatch.

If you have seen unsatisfactory results using registered insecticides, it may be worthwhile to review sprays records. Some applications have been applied too late to achieve optimal control of nymphs.

What can we do differently in 2021?

Chinch bug infestations have been an emerging problem across residential areas for the last decade. In 2019 and 2020, chinch bugs haven’t just emerged, they have cemented themselves as the biggest insect-related challenge for homeowners and lawn care companies that try to control them. In developing sustainable chinch bug control programs, it is important to utilize the full spectrum integrated pest management (IPM), including cultural and chemical remediations.

Scouting and monitoring.

Increasing your frequency of scouting early in the season is the most critical component of a successful IPM strategy. Scout first in areas close to overwintering habitats that receive full sun. This would be near mulch piles, patio or decking structures, or along fencing or foundation walls. From April through the first half of June the vast majority of chinch bugs that you will see are fully developed adults. From the second half of June through August, chinch bug nymphs will dominate the population.

Scouting for the initial appearance of first instar nymphs is critical. These first instar nymphs can be very difficult to see. They do not tend to be readily visible on sidewalks or high up the leaf base. First instar nymphs are typically found very close to the soil layer near the thatch and plant stem. An effective scouting technique that anyone can use is the modified flush technique.

A modified flush technique requires the use of a plastic or metal cylinder (such as a soup or coffee can) and the removal of both lids of the container. Lightly pound the canister into the ground with a rubber mallet so that the container is approximately five centimetres in the ground. Fill up the canister with water and keep refilling the canister to ensure water isn’t draining too quickly. After 30 seconds, chinch bug nymphs and adults will float to the surface. Count the number of chinch bugs that have surfaced. A common threshold to determine if a spray application is necessary is approximately five to eight chinch bugs per 15-centimetre diameter using a coffee canister. This sampling should be done at several locations within a lawn and replicated weekly to observe trends even after a chemical treatment.

Cultural control.

Fertility. Maintain adequate nitrogen fertility during spring, summer and fall. Lawns deficient in nitrogen will have less energy and have a lower recuperative potential to tolerate chinch bug feeding. Late summer or fall fertilization can be effective in recovering compromised lawns.

Irrigation. It is important to irrigate lawns to prevent wilt stress during the summer months to prevent further turfgrass decline. Turf grown on south-facing slopes in full sun may require more water than areas grown in shade.

Overseeding. Introducing endophyte-enhanced grasses will improve the lawn’s tolerance to chinch bug activity. Endophytes are non-pathogenic fungi that can allow for reduced inputs on residential lawns and can help reduce chinch bug damage.

Mowing. It is best to cut and maintain the lawn at a height of five to eight centimetres during the summer months. It is important to mow at the rate of growth. The rule of thumb is to not remove more than one-third of the leaf tissue when mowing. Maintain sharp blades to prevent a ragged cut that could result in moisture loss and decreased turf quality.

Biological control. Naturally occurring biological controls have been identified for chinch bug management. The pathogenic fungus Beauvaria bassiana has shown to be able to reduce chinch bug populations. There are several new Beauvaria bassiana-based products that were recently registered by the PMRA. After spreading the biological control agent, the manufacturer recommends keeping the ground well “humidified” to enhance the efficacy and spread. In an active outbreak, these products may need to be reapplied at three-to-five-day intervals.

Chemical control

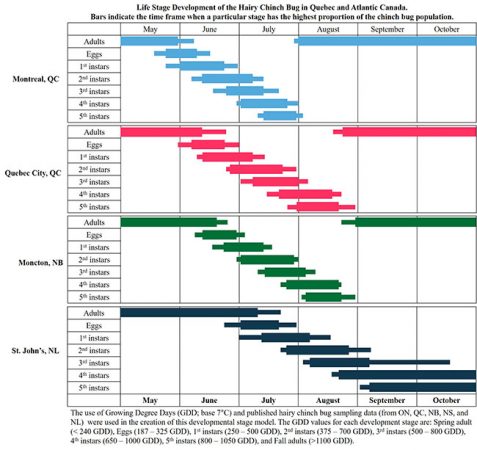

Effective application timing. Several variations of growing degree day (GDD) models have been developed for Ontario, Quebec and Atlantic Canada. The most common base temperature is seven degrees Celsius. Using this number, peak egg development occurs at 187-340 GDD, and first instar nymphs are observed between 250-500 GDD. Peak damage caused by third and fourth instar nymphs occurs between 500-1000 GDD, which will be from early-to-mid July for most years, depending on the region (see chart). Monitoring the lifecycle of chinch bugs through scouting and monitoring, as well as tracking growing degree days, it is now possible to plan an action plan.

Product selection. Many insecticides and entire classes of chemistries have been banned for residential use. This includes many of the older pyrethoid insecticides (such as bifenthrin) and all neonicotinoids (such as imidacloprid and clothianidin). There are now only two synthetic chemistries that are currently labeled for chinch bug “control” in residential spaces:

DeltaGard SC is an effective, fast-acting contact insecticide labeled for control of chinch bugs, ants, cutworms, webworms and ticks. This product should be applied in enough water volume to achieve deeper coverage into the turfgrass canopy.

Tetrino is a broad-spectrum systemic insecticide that contains the active ingredient Tetraniliprole for rapid plant uptake and translocation. It provides strong systemic activity for many root- and surface-feeding insects – including chinch bugs and white grubs. Repeat applications at 28-day intervals may be necessary for large chinch bug populations.

Early season timing. For chronic chinch bug infestations, consider a spring adulticide application of DeltaGard SC just prior to egg laying. This application should be made before 200 growing degree days (base seven degrees Celsius) have accumulated. In most years, this application timing occurs in mid-to-late May, depending on the weather. Adding a systemic insecticide such as Tetrino in this application will improve control of spring adults and provide protection against younger nymphs after egg hatch.

Mid-season timing. A sequential application of a DeltaGard and Tetrino and systemic insecticide should be applied when third instar nymphs reach peak activity. This tends to occur in early-to-mid July, when cumulative growing degree days are between 500 and 800 (base seven degrees Celsius). Adding Tetrino at this time provides improved chinch bug control and control of annual white grubs, such as Japanese beetle or European chaffer.

Other considerations. Applications for chinch bug control should be applied in a sufficient water volume to ensure the spray solution is driven towards the base of the plant near the thatch layer.

Print this page