Features

Earth Week

Eco-Friendly Soils

The amazing world beneath our feet speaks volumes

Soil is a living and breathing entity – one that should be appreciated and respected

February 22, 2021 By Alan Dolick

There are many indicators that suggest we have a mere 60 years of topsoil remaining on our planet – a very scary thought when you really stop and contemplate the consequences. Considering how important the soil is to our profession, we give it a relatively small amount of thought when creating a strategy to maintain healthy turf. Most view the soil as merely a substrate to hold plants upright and to deposit nutrients. The reality is that soil is a living and breathing entity – one that should be appreciated and respected.

Having a sense of the vast ocean of activity that is below our feet is the first step in understanding the importance of a healthy soil ecosystem. Packed with an enormous amount of life, ranging from microscopic single-celled organisms to large insects, and everything in between, soil is brimming with life and energy. All of these organisms function as one incredible ecosystem, ultimately regulated and influenced by the plants that sit atop this medium.

We all know that plants can make their own food by way of photosynthesis, but many are not aware that they give away approximately 40 per cent of what they create. Plants are the catalyst for the life in the soil by way of food that they provide to the microorganisms. Plants produce exudates, which are sugar and amino acid-based compounds that are pumped out of their roots, stems and leaves.

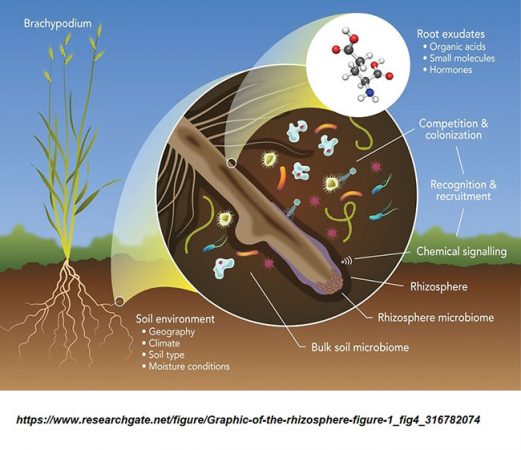

In this case, root exudates provide nourishment to the bacteria and fungi living close to the root in a narrow band of area referred to as the rhizosphere. This area, usually only a millimetre or two around the root surface, is an absolute frenzy of microbial activity.

A single plant’s rhizosphere can contain more microbes than there are people on the planet. In a healthy teaspoon of soil, there is up to 70,000 different species of bacteria and more than 500 types of fungi, with numbers totalling in the billions, if not trillions1. Considering their size, it’s remarkable to ponder the vital role these invisible organisms play in the health of plants, our food and ultimately all of us.

Another extraordinary aspect of these microbes is that they all have specific functions. Depending on the plant’s need at a particular moment, compounds within the exudates can be subtly altered to cause specific microbes to multiply, providing whatever necessary component the plant may need.

Microbial interactions can be broken down into a hierarchy of predator-prey relationships, beginning with bacteria and fungi. They are the backbone of this network, constituting the largest percentage of biomass in both actual numbers and weight. Without robust communities of both families of organisms, the entire system falls apart.

Unaccounted-for nutrition

When we think about nutrients from a plant’s perspective, we usually lean towards the minerals that are in the soil and the fertilizer that we apply. However, there is a considerable amount of nutrition that is unaccounted for inside the living organisms in our soils, and the more we increase the numbers within these microbial communities, the more nutrients we have available to our plants.

Bacteria, the smallest life form on our planet, are about 60 per cent protein and therefore a major source of nitrogen. In fact, they serve as nitrogen sinks, capturing it and internalizing what would otherwise leach out of the soil, volatize, or denitrify into the atmosphere.

These microscopic organisms should really be viewed as tiny bags of fertilizer2. Bacteria have the highest concentration of nitrogen of any living organism on the planet, with a carbon to nitrogen ratio of five to one. This ratio is a vital component to nutrient cycling and is the basis for understanding how this predator-prey relationship affects microbial balance and the health of plants living in that ecosystem.

Microscopic predators called protozoa will feed on upwards of 10,000 bacteria per day, releasing plant-available nutrition as they go. Protozoa have a carbon-to-nitrogen ratio of 30 to one and are largely interested in consuming the carbon component of the bacteria. Plants are the benefactors of this dynamic relationship because the protozoa now have an abundance of nitrogen in their system that they need to “give away” to maintain their internal carbon-to-nitrogen balance. The form of nitrogen that protozoa excrete out into the soil has been complexed into an organic form, meaning it is immediately plant-available and requires substantially less energy and water from the plant to convert it to proteins and enzymes. This increased efficiency creates a much more resilient plant, one that will be better able to manage the stress of a hot, dry summer.

Bacteria provide a host of other benefits beyond just an organic source of nitrogen to the plant. They also help mineralize and store all the other nutrients required, they provide the basis for soil aggregation, they decompose organic material, encapsulate toxins, and protect the plant from disease. For instance, when in high enough numbers, pseudomonas bacteria will actively police the soil, searching out and consuming pathogenic fungi3.

While bacteria can be classified as primarily mineralizers, fungi provide a slightly different function by transporting carbon into the soil. Like bacteria, fungi have a bad reputation in the turf world as causing disease. While this is true for a select few species, the vast majority of fungi in the soil perform beneficial functions for the plant.

While fungi are excellent at transporting nutrients, water, carbon, and even bacteria with their hyphae (tube-like structures), they cannot produce their own food. For this, they are completely dependent on plants for nourishment. Everything in nature must be viewed as a supply and demand relationship; a plant is not going to provide food for another organism if it is not getting a return on its investment.

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi

Let’s take arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) for example. Perhaps the most well-known type of beneficial fungi, it creates a hard-wired connection to the plant by impregnating itself into the root. A healthy AMF network can have up to 10 miles of hyphae in a cubic foot of soil and can increase the surface area of the root system up to 100,000 times4. Not only will the increased surface area provide more absorption sites for water and nutrients, it also acts as a defence mechanism for the plant, excreting compounds that stifle development of diseases, attacking root-feeding nematodes and creating a physical barrier to infection sites.

The AMF have also been shown to reduce weed populations. In a study conducted by Rinaudo et al, total weed biomass was on average 47 per cent lower in plots that were inoculated with AMF than those plots that had no association5. This is likely because many of the weeds we see in turf settings do not associate with AMF. The turf that has created this association with the AMF is now better equipped to extract nutrients and water from the soil, ultimately outcompeting the weeds for resources.

Soil fungi are also incredible decomposers of thatch and all other organic materials. Without their help, all plant material that has ever been produced on this planet would still be here. Having a thriving community of fungi in the soils you maintain will help keep thatch to a minimum, along with all the associated problems that come with excessive buildup of organic material.

There is so much to this wonderful world below our feet and we are just scratching the surface of our understanding of nature’s capabilities. We must understand that nothing in nature is by accident or wasted energy. Everything is here for a reason and performs a specific function.

Let us begin to work together to provide a new way forward – one that reduces your costs, improves plant performance, minimizes personal anxiety, and, most importantly, reduces our impact on the environment so we can be proud of what we leave behind for future generations.

Alan Dolick is eastern Ontario sales representative for Evergreen Bio Innovations, formerly Lawn Life Natural Turf Products.

References

- Ingham “Soil food web foundation course” 2019

- Lowenfels “Teaming with Microbes” 2006

- John Kempf “Quality Agriculture: Chapter 1 Michael McNeill, Developing disease resistant and regenerative soil health” 2020

- Lowenfels “Teaming with Microbes” 2017

- Riaudo et al. “Mycorrhizal Fungi Supress Aggressive Agricultural Weeds” Plant and Soil 333 nos. 1-2 August 2010

Print this page