There are eight basic steps to remember when maintaining sports fields to ensure they are both playable and properly conditioned, members of the Sports Turf Association were told at the organization’s 26th annual field day in Mississauga, Ont. in September.

Forgetting even one or two of these simple and straightforward steps can lead to a field which can be compromised, rendered unsafe or not play up to users’ expectations, said Jeff Fowler, cooperative extensionist from Pennsylvania State University.

Over the past 25 years, he said he has seen a trend develop at several of the sports facilities he has visited in which those looking after athletic fields are “going 99 miles an hour in a 35-mile-an-hour zone” and seem to have far too much on their plates to ably accomplish what needs to be done.

Fowler’s eight recommended steps begins with soil testing.

“Soil testing is taking the blood pressure of our soil.”

A soil test will give the sports turf manager a “prescription” of how problem soils can be remedied. Several samples should be taken from various locations of a field, dried atop newspaper, bagged and sent to a laboratory for analysis.

Samples will be different for every field and every location. A key recommendation from a soil test will be the amount of lime or fertilizer needed for the soils so that the fields can perform at the highest levels.

Fowler said soils on fields in the Pennsylvania area tend to be below optimum pH levels, requiring lime to bring them to ideal levels. Liming and fertilizing sports fields as required is the second step sports turf managers need to be remember, he said.

“Cool season grasses do best between 6.0 and 7.0 (pH levels),” he said, but acknowledged a level of at least 6.5 reaches the optimum point where macro and micronutrients are most readily available for plants to uptake.

Raising the pH to an ideal level takes more lime on “mucky” soils than it does on sandy and silty soils, he added.

Between three and five pounds of nitrogen per 1,000 square feet will help maintain Kentucky bluegrass fields at a high level, Fowler said, noting some fields growns to newer tall fescues perform well with less nitrogen requirements.

Fowler’s third suggested step is aerification, with the particular need for core aerifying.

“At some point in time we need to pull cores on our athletic fields.”

Sports turf managers can adopt various other methods of aerating their fields, but will eventually need to pull cores, he said. The time of year for coring isn’t a particularly important consideration for sports fields, as long as it’s done, he added.

Baseball fields can be core aerated in the fall when the season ends, but it’s not the most ideal time for football.

“Research shows that every square foot should have 35 three-quarter-inch holes poked in it annually.”

Fields which serve multiple purposes will see compaction in different areas. When used for football, most compaction will occur down the centre length of the field between the 20-yard-lines. Much of the compaction which occurs from soccer games will be in the goalmouth areas.

Fowler said core aerification should be done to the point where the field looks like it has been rototilled. Other forms of aerification can be done at various times throughout the season.

“There are lots of ways we can aerify without disturbing play throughout the year.”

Fowler’s fourth recommended step is overseeding which, he said, doesn’t require the use of an expensive overseeder. A fertilizer spreader can be utilized to tackle heavy wear areas on a field.

He shared a story about a school district which was having issues with the conditioning of its soccer field. One individual was responsible for its upkeep and, for Christmas one year, gave a gift of a five-gallon pail of perennial ryegrass seed to the local soccer team’s goalkeeper. The goalkeeper was instructed to bring the pail with him to each practice and, at the end of each session, to throw a handful of grass seed into the goalmouth. The Christmas gift also included a booklet of coupons for free refills of seed.

“It worked,” Fowler said of the unique and cost-efficient method of overseeding a heavy wear area. “He had better goalmouths than he ever had. He was constantly filling in those divot marks with new grass seed to fix those worn out areas.”

A study done in Ohio, which was replicated at Penn State, involved throwing out large amounts of grass seed at one time.

“So if our plan is to overseed 10 pounds per 1,000 square feet of perennial ryegrass over the course of the entire year, this study says to throw it all out at once and let the seed bank rejuvenate itself.”

Topdressing is Fowler’s fifth recommended step. Several years ago, the proper type of topdressing was debated—should it be topsoil, should it be sand? Most of the fields he deals with are native soil fields.

On fields Fowler utilizes for his research, compost, USGA sand and native soil/topsoil whose particle size was similar to that of the existing field were studied. On a baseball field, the left field side of the outfield was left alone. In the centre field area, he shallow-tine-aerified it before spreading topdressing of calcined clay, sand and compost in six-foot-wide swaths. He tested for surface hardness, moisture and temperature, and found there was no difference between deep and shallow tine aerification or with either of the three types of topdressing material.

The difference, Fowler said, was the practice of aerification and topdressing which made the field quality better, no matter the method of aerification.

“In left field, where we did nothing, it was not as good. It was the simple practice of topdressing and aerifying which made the difference.”

Topdressing must be practised hand in hand with aerification, Fowler said, adding topdressing alone will produce layers “that will make a big muddy, mucky mess.”

Paying attention to transition areas of a field is Fowler’s suggested sixth step. These are the areas on ball fields where turfgrass and the dirt or skinned areas meet.

Inattention to these areas on a field often leave lips which result in both unsafe conditions and uneven playing surfaces that can affect the game’s playability.

The problem is often caused by trucks on fields which drag steel beams at high rates of speed. Slowing down when dragging the skinned areas will help keep material where it belongs, Fowler said.

He said one should be able to straddle a transition area with one part of the foot on turfgrass and the other half on dirt and not feel any elevation change.

“Pay attention to those lips by constantly edging.”

Either power or hand-powered edgers can be used to keep edges sharp and prevent buildup of lip-producing material in transition areas.

Fowler’s seventh step is mowing which should be done frequently enough so as to not remove more than the top third of green growth in a single mowing.

“Mow as high as you can get away with, as high as your users will allow you to get away with.”

It’s the roots which sports turf managers need to worry about most, Fowler said, and not what is seen at the surface.

Mower blades must always be kept sharp, he added. Grass blades will heal better when cut by a sharp blade, and the field looks better to users.

Maintaining the playing surfaces is Fowler’s eighth step. Maintenance should be done effectively enough to ensure water flows off the surface. Sports field managers can’t always rely on water to move through the profile.

Improving surface drainage can be accomplished through laser leveling or by constantly working the area with a nail drag and box drag.

Although his presentation covered the eight steps he personally saw as vital to best field maintenance, Fowler offered a ninth step: communication.

“If we don’t have the ability to communicate with our players, with our coaches, with our administrators, with our parents…we have no ability to do our jobs effectively.”

One who wishes to speak with a higher up, to secure additional funding for seed or other material, will see his chances for success improve significantly if he is an effective communicator, Fowler said.

He recalled an incident in which a sports turf manager used crumb rubber in the goalmouth of a soccer field to help protect the plants’ crowns and reduce wear. The soccer organization was so impressed with the improvement of the field that it offered to pay for enough crumb rubber to do the same for other goalmouths.

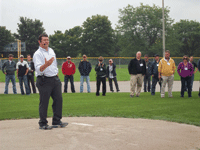

Fowler led his audience outside to a baseball diamond at the Mississauga Valley Community Centre and Park, to show which areas of the field required special attention.

He said the area of highest maintenance on any baseball field is the pitcher’s mound.

“Every single play of every single game in the game of baseball starts here. It’s the area of heaviest wear and thus turns into the area of heaviest maintenance.”

Several things must be done to maintain this area, including the ability to get water to it. Water is the “glue” which holds together the sand, silt and clay. This is important on all skinned areas of a baseball field, he said.

If separated, the silt and clay particles “will go home on everybody’s uniform and will work their way into the transition area where we will have a lip form.”

Most wear on the pitcher’s mound occurs in front of the rubber, from which a pitcher steps off, and into the landing area. That area can be cut out and filled with four to six inches of heavy packing clay to help reduce wear. It should then be covered with the appropriate skinned infield material.

In his leisure time, Fowler manages a Little League team and instructs his pitchers not to dig into the area in front of the pitcher’s rubber. He said his instructions are not for reasons of creating unnecessary wear, but because his pitchers would be shortchanging themselves by reducing the 10-inch elevation advantage they have on opposing batters.

“It makes no sense to dig a hole deeper to get lower. The higher up I am, the more advantage I have over the person trying to hit the ball.”

In “digging down,” the pitcher is trying to get some additional footing which makes it important to provide heavy packing clay in the landing area of the mound before covering it with the appropriate mix. Pitchers will be given the footing they need at the surface without the need to dig down.

“The hole today is a puddle tomorrow and a rainout the next day.”

Fowler’s son worked as an intern this summer for the Kansas City Royals and spent 90 per cent of his work day with another member of the team’s 10-person grounds crew maintaining the mound and ensuring its slope was perfect.

He said there are several ways to keep material on the skinned areas where it belongs to prevent it from creating a lip in the transition area. A stiff-bristle broom requires only one pass around a field in a single day. Hand tools, such as an iron rake, can also be used in a couple of directions.

Fowler said he likes to take a pressure washer or high-pressure hose to blow dirt from out of the grass and back into the skinned area at the end of a season. He said another method is to use a backpack vacuum and suck the material from the edge of the grass to prevent lip formation.

Acknowledging that herbicides can no longer be used to control broadleaf weeds on Ontario sports fields, Fowler said an effective alternative method to crowd out weeds is to overseed.

“And keeping the grass healthy through proper fertilization gives it plenty of food to outcompete the broadleaf weeds.”

Print this page